Cyril Moshkow,

Jazz.Ru Magazine editor

This humble research was ignited by a simple question from a curious European jazz specialist: if we want to perform the Russian material in jazz, do we have to stick with Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, and Mussorgsky —or Russian jazz musicians have their own corpus of standards they draw from?

In brief: both. Many Russian musicians created impressive jazz compositions based on the material from the great trove of Russian classical music, the works by not just the three composers mentioned above, but also Glinka, Balakirev, Rimsky-Korsakov, Borodin, Scriabin, Prokofiev, Sviridov, and other Russian classical authors from the 19th and 20th centuries. But they also have an equally vast trove of Russian popular songs from the 1920s, 30s, and on to 1980s — the so-called Soviet Song Classics: tunes from certain Soviet-era movies, still watched today and loved by millions; pop songs or show tunes from the past decades, still listened to today because of their cultural significance; and even TV shows theme songs! Wasn’t the American corpus of jazz standards formed from similar sources, along with the tunes composed by jazz musicians? Each big country with a large population and a long history has its own musical culture to be inspired with, so it’s no surprise that Russian jazz musicians not only draw inspiration from American sources, seeking to master the same musical language as their counterparts elsewhere in the world, but also have a rather significant list of Soviet / Russian tunes to treat as jazz standards. Here’s a dozen of such tunes, with their originals and a few chosen jazz versions for each — in four episodes, three songs in each. Thanks for the question, Arlette Hovinga!

Earlier in the series — Episode 1 of 4: And Snow Still Falls; Dark Night; Tired Toys Are Sleeping

4. Good Mood Song (Песенка о хорошем настроении)

by Anatols Liepiņš (1907-84), lyrics by Vadim Korostelev

The movie this song first appeared in, The Carnival Night (1956,) had an enduring cultural significance as the first post-Stalin-era Soviet musical comedy. For the first time in years and years, jazz was represented in that film as a positive force, as part of modern Soviet culture, not as part of the rotten decadence of the capitalist West as it was usual before Stalin’s death in 1953. The songs composed for the movie by the Latvian composer Anatols Liepiņš were not exactly American modern jazz of the mid-50s but rather old-fashioned jazzy/swingy pop from earlier decades, but for the Soviet audiences even that was a gulp of fresh air; the debut film by Eldar Ryazanov, who ended up one of the most successful Soviet filmmakers of the following four decades, sold nearly 50 millions cinema tickets in 1956. Another innovation was the recording technology used for The Carnival Night; for the first time in Russian history, the big band score was pre-recorded by the Moscow-based Eddie Rozner Jazz Orchestra, and Lyudmila Gurchenko was singing to their pre-recorded playback in an empty studio with earphones on her head. Witnesses said that almost entire Mosfilm studios personnel assembled behind the studio glass to watch this modern technology wonder to happen.

If the video link doesn’t work in your country (which it may, as the video rights owners restrict free usage outside Russia,) use the Spotify link instead.

Jazz Versions:

1977, Melodiya Ensemble: active 1971-1991, it was the Melodiya label studio band led by alto sax player Georgy Garanian, which employed fine jazz soloists and arrangers. Trombone solo: Konstantin Bakholdin, soprano sax solo: Alexei Zoubov

2012, Moscow-based neo swing group Stilyagi Band live at the Union of Composers jazz club

Singer Anna Buturlina, 2017 (featuring pianist Daniil Kramer)

1980s pop star Albert Asadullin & Oleg Kuvaitsev Jazz Band, Saint Petersburg. Lockdown online version, 2020

2020: young saxophonists from Saint Petersburg Krasnoselsky Performing Arts School for Children, lockdown online version

2020, singers Armine Sarkisyan, Mariam Merabova, and Anna Buturlina; on two pianos: Daniil Kramer and Valeri Grohovski (Russia Kultura TV concert for pianist Daniil Kramer’s 60th birthday)

2021, Russian TV First Channel, morning show: TV personality Olga Stupina performs the song live at the Red Square in Moscow with her jazz band while playing the acoustic bass herself. Maybe it’s not the finest example of jazz singing, but quite original nevertheless. January is not the warmest month in Moscow: note her cello player’s expression.

5. I Asked The Ash Tree (Я спросил у ясеня)

by Mikael Tariverdiev (1931-1996), lyrics by Vladimir Kirshon

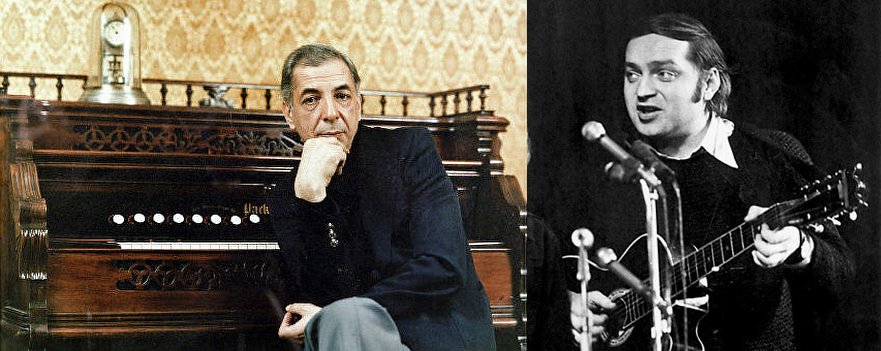

The original version appeared in the 1975 Soviet TV two-episode mini series, The Irony of Fate, or Enjoy Your Bath!, filmed by none other than the very same Eldar Ryazanov, 20 years after the overwhelming success of his debut movie, The Carnival Night (see above.) The series were first aired on the 1st channel of Soviet TV on December 31, 1975, and became the staple for the New Year’s Eve TV programming ever since. It featured several songs composed by Mikael Tariverdiev, which remained popular —and loved by millions— 45 years later. The original vocalist and guitar part performer, folksinger Sergei Nikitin, did not appear on the screen: the film protagonist, played by Andrei Myagkov, lip-synced to Nikitin’s voice.

Jazz Versions:

Led by famed saxophone player and producer Georgy Garanian (1934-2010,) the Melodiya Ensemble, Soviet recording monopoly’s Moscow-based studio band, first recorded an easy listening / contemporary jazz version of the tune with Garanian’s solo on alto sax shortly after the song’s premiere in 1976. This version was re-released several times, the latest on Timeless Songs («Проверено временем»; MEL CD 60 01320, 2007)

An unusual version was performed in 2021 by Joander Santos, Brazilian singer, guitarist and percussionist who resided in Russia for several years. The unofficial Brazilian music ambassador in Russia, Joander arranged the song for a jazz big band and performed it at a jazz festival in the city of Ufa with the Bashkir State Philharmonic Big Band led by Oleg Kasimov.

3. Moscow Nights (Подмосковные вечера, literally Evenings in Moscow’s Suburbs) a.k.a. Midnight in Moscow

by Vasily Solovyov-Sedoy (1907-1979,) lyrics by Mikhail Matussovsky

The song was originally commissioned for an insignificant documentary film in 1956 and never meant to be popular; both the composer and the lyricist regarded their hastily done job as a flop; the most popular singers of the period refused to record it, and it was laid on tape for the movie by a drama actor who could sing. All of it changed overnight, when Moscow radio played it once, and not in the prime time at that. The next morning, the local post office was drowned in requests, and the song was replayed on the All-Union Radio again and again every day, until by 1957 the whole 200-million country knew and could sing it, and the humble documentary tune became the official theme song of the 6th World Festival of Youth and Students, the international event which brought to Moscow 34,000 delegates from 130 countries and testified to the social and political changes during the post-Stalin liberalization of the Soviet regime, the so-called Khrushchev Thaw. American classical pianist Van Cliburn, the first U.S. musician to win the Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow in 1958, learned the tune while in the Soviet Union and brought it to the States, but the place outside Russia where the song became especially popular was mainland China.

Jazz Versions:

Unlike other tunes on this list, the song entered international jazz repertory quite early, and still is relevant today. The U.K. trad jazz band Kenny Ball and His Jazzmen made it a hit: their 1961 recording, titled Midnight in Moscow, peaked at #2 in the U.K. Singles chart in January 1962, spent three weeks on the U.S. Easy Listening chart, and reached #2 in Billboard’s Hot 100 in March, 1962. Their version laid the pattern for numerous Dixieland / trad jazz versions around the world — and, of course, especially in Russia, where almost every Dixieland jazz band with any significant self-esteem had this (or similar) version in their repertoire.

Swedish pianist Jan Johansson recorded the tune on his 1967 album, Jazz på ryska (Jazz in Russian,) in a more modern version as Kvällar i Moskvas förstäder (the literal translation of the Russian title into Swedish.)

Nearly 40 years later, Swedish pianist Jan Lundgren with fellow Swede, bassist Mattias Svensson, and the Bonfiglioli Weber String Quartet recorded their own version for ACT on their 2016 Jan Johansson tribute album, The Ystad Concert. They did not mention the original composer, though, stating that the song was «traditional.»

In 1978, the Melodiya Ensemble led by Georgy Garanian, this time as an enhanced big band with added solo on balalaika (Russian three-stringed folk instrument,) recorded a four-minute modern jazz big band version of the tune for the Moscow World Service, the Soviet Union’s 24-hours shortwave radio channel in English. I could not find a better recording: this was taped in early 1980s off Moscow World Service AM (middle band) broadcasting. Note the rich orchestral texture in Garanian’s arrangement. The first minute of this recording served as the station’s hourly call sign, while the full version was used for the occasional programming gaps.

In 2015, Russian pop singer Valery Syutkin, himself an avid jazz fan, recorded a pop-jazz version of the song for his Syutkin Light Jazz album, featuring the Russian jazz scene veteran, guitarist Alexey Kuznetsov.

In 2013, during their Russian tour, the French-Italian trio Marc Berthoumieux / Giovanni Mirabassi / Laurent Vernerey performed their own version of the tune (video from their concert in Vladivostok, in the Russia’s Far East.)

Estonian jazz / improv / electronica / indie pop star, Kadri Voorand, performed a highly unusual experimental improv version of the song in original Russian (which she studied as one of the foreign languages in high school) during her 2015 Russian tour. This video is from her performance at Moscow’s Esse Jazz Club :

Finally, the Slovenian neo swing band Pickpocket Swingers performed their post-modern version of the song in original Russian, but with a strong Yugoslavian accent — which, for a Russian ear, was actually rather cute! (Music video by RTV Slovenia)

Episode 3 of this series is scheduled for June 5, 2021.